- Barry Yeoman: Unabridged

- Posts

- Flashback to my baby journalist days

Flashback to my baby journalist days

Standing up to authority in the face of intimidation. Plus, the places where I'm finding encouragement.

Yours truly doing editor things, 1978.

Dear friends,

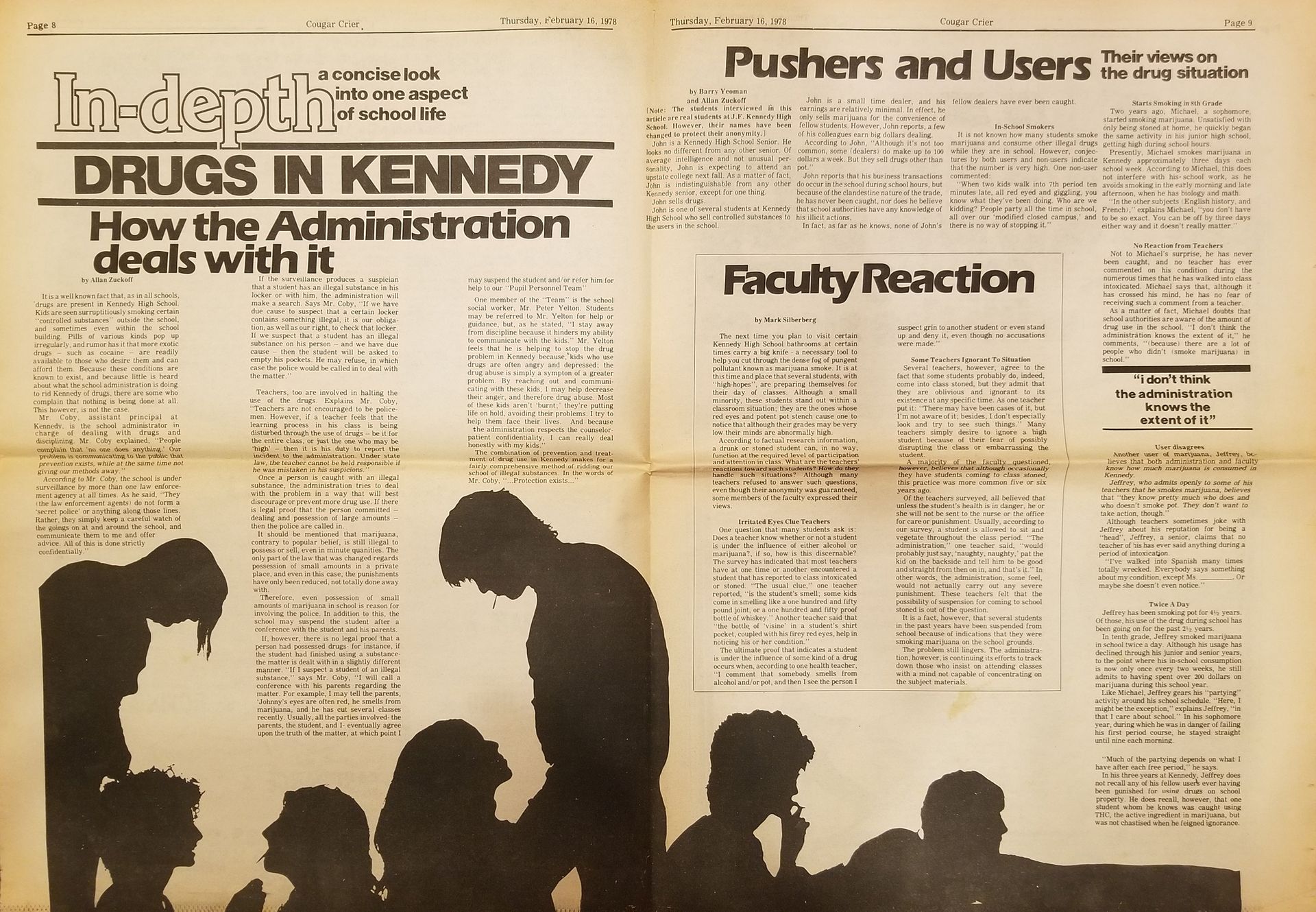

By February 1978, I was persona non grata in the principal’s office at J.F. Kennedy High School in Bellmore, New York, where I was co-editor of our student newspaper, The Cougar Crier.

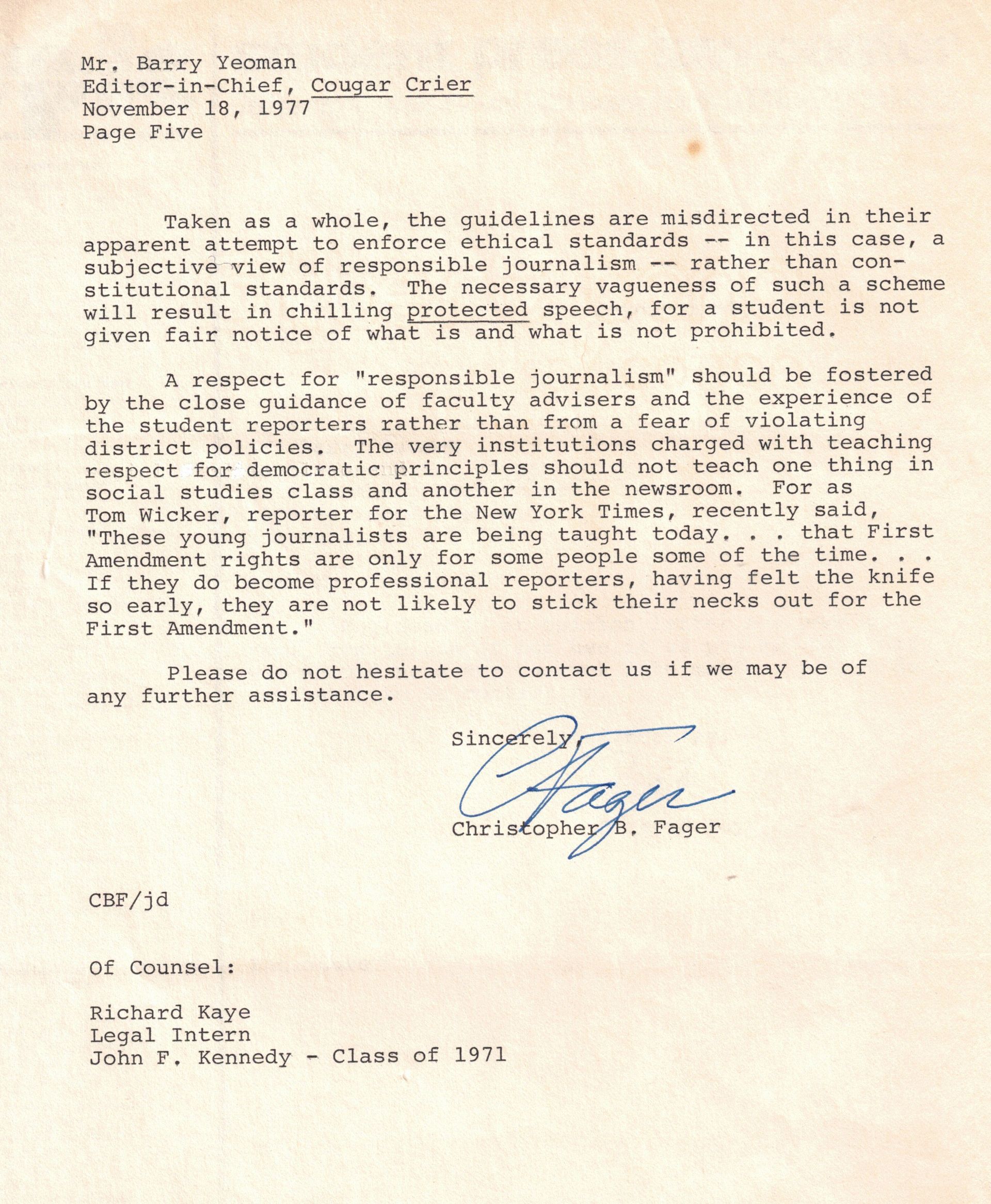

I had started my tenure by throwing down the gauntlet. I unearthed a districtwide policy that limited what could be published in school newspapers and created a mechanism for advance review and censorship. That struck me as a pretty clear violation of the First Amendment, so I did what any fiery 17-year-old journalist might do: I mailed a copy of the policy to the non-profit Student Press Law Center and asked what its attorneys thought.

The Center responded with a five-page opinion: The policy violated the landmark Supreme Court case Tinker v. Des Moines, which extended free-speech rights to public-school students. “The very institutions charged with teaching respect for democratic principles should not teach one thing in social studies class and another in the newsroom,” the Center’s director wrote to us.

That letter sparked some long public meetings, including at least one where I spoke. We won the backing of the Parent Faculty Association and student government. The issue went all the way to the Board of Education, which passed a revised policy guaranteeing students “complete freedom of the press.”

We had won. Certain adults were unhappy.

My co-editors and I took our civil rights seriously. Our first issues of the Cougar Crier explored abortion, academic tracking, sex education, and the demise of student activism (“Why Johnny Can’t Riot”). We moved our page-layout process in-house, rather than relying on our printer, so fewer adults could peek over our shoulders. We burned through two faculty advisers before we got handed off to a 28-year-old guidance counselor who was so low in seniority that he couldn’t refuse the assignment.

Our new advisor was nervous enough that he still let our principal read the most controversial articles before publication. The principal, Mr. Tannenbaum, didn’t interfere—until February, as we were readying a two-page spread about drug use on campus.

In particular, Mr. Tannenbaum was rattled by my interview with a college-bound senior who was earning pocket change by selling marijuana at school.

The interview, honestly, wasn’t very interesting. (I would have benefited from taking a journalism class.) The most revealing thing the dealer said was that some of his peers made up to $100 a week selling harder drugs on campus, and that none had been caught.

But Mr. Tannenbaum really didn’t want to see the article published. Before we went to press, he called me into his office. Here’s my best memory of the conversation 48 years later:

Mr. Tannenbaum: Who is the dealer?

Barry: I can’t tell you.

Mr. Tannenbaum: I’ve talked to the school board’s attorney. He said that if you don’t tell me, then you’re an accessory to the crime of drug dealing, and he directed me to report you to the police.

Barry: If we don’t publish the article, do you still need the name?

Mr. Tannenbaum (after thinking for a moment): No, I don’t.

Barry: Then you don’t really want the name. You just want us to kill the article. And that’s censorship. So we’re going to publish.

With that, we sent the pages to the printer. To spread the risk, my friend Allan bravely agreed to share the byline.

After we distributed Issue No. 5 of the Cougar Crier in every homeroom, Mr. Tannenbaum called me back into his office and notified me that the police would be coming for me.

You can guess what happened next: nothing.

But I didn’t know what to expect at the time. I was a skinny, stuttering teenager with college ambitions, and Mr. Tannenbaum (I believed) had the power to tar me with a criminal record or even withhold my diploma. Still, I knew even then that a free press required courage to defend. I think of that today whenever I see a news executive bend to an authoritarian demand.

Plus, where I’ve been finding encouragement:

Adam Bonica’s column on why resistance isn't futile. “Hidden corruption persists because it is difficult to mobilize against,” writes the Stanford political scientist. “Exposed corruption shifts the axis of politics from left versus right to clean versus corrupt, people versus oligarchs. That’s a fight authoritarians lose.” One sentence from his column that sticks with me: “The wall looks permanent until the day it comes down.”

John Noltner’s multimedia series The Troubles. Last summer, John traveled to Northern Ireland, which was torn apart by decades of sectarian conflict. He interviewed artists, educators, peacebuilders, and everyday people who are forging creative solutions to heal old wounds and imagine a better future. His series combines photography, podcast, text, and a healthy portion of hope.

What else I’ve been reading:

Laura Jedeed on how she got a job offer as an ICE agent—despite her public reputation as an anti-ICE journalist.

Robert Samuels on the Afghan refugees who now must navigate a more hostile America.

Alex Burness on the American Samoans who face prosecution for voting in their own country, the United States.

s.e. smith on the language phenomenon called "algospeak."

Music I’m listening to: “Audience With the Queen,” a big-hearted collaboration between 84-year-old soul queen Irma Thomas and the funk band Galactic. Check out this synergy of New Orleans heavyweights:

I learned about “Audience With the Queen” from my friend Craig Havighurst, a musician, writer, producer, and radio host who lives in Nashville. It’s part of his list of 30 outstanding Americana records from 2025.

Meanwhile, I’ve got some stuff in the works. Keep you posted.

All best,

Barry Yeoman